Old Saint Joseph’s, Willings Alley

Old Saint Joseph’s is a small church located in Willings Alley in Philadelphia and it is run by the Jesuits. Willings Alley is located in the Society Hill section of Philadelphia between 3rd and 4th Streets below Walnut St. A large portion of the material for this treatment was taken from a book named “Life of Father Barbelin SJ” by Eleanor C. Donnelly, published privately in 1886. There are very few copies of this book still available, and it is mostly found in rare book collections. To some extent this book is written in the style of a “vita sancti”, and so it does not translate well into the modern idiom. Nevertheless it provides a fascinating insight into the colonial life of Philadelphia, and the issues relating to religious tolerance in the British Colonies. Roman Catholicism now enjoys the status of a main stream religion, but in colonial times this definitely was not the case.

The picture below is “A colonial street scene in a modern city”. Of course it is Willings Alley, and Old Saint Josephs is located just behind the photographers left shoulder. It gives the viewer some sense of the dichotomy between modern and colonial times.

The following is from Eleanor C. Donnelly’s book:

Father Greaton’s Popish Chapel

To this, our old City of Brotherly Love, (where Longfellow thus located the exiled Evangeline,) came the early Jesuit missionaries from Maryland in the seventeenth century, to attend to the spiritual wants of its few Catholic inhabitants. As early as 1686, only four years after the settlement of Pennsylvania, Mass was said in certain private houses in Philadelphia, being offered for the first time in our city, some say, by a Father Harvey SJ., but, as is stated more authentically in the Woodstock Letters, by Father Harrison of the Society of Jesus; and the adorable Sacrifice of the altar continued to be offered, and the Sacraments administered secretly by holy missionaries of the same Society, for nearly half a century thereafter. They could only officiate in private, however; and in public, were always disguised.

During those fifty years of arduous and difficult ministry on the part of the sons of St. Ignatius, the Catholic element in Philadelphia increased to such an extent, (presumably by the influx of Irish emigration,) that their religious Superiors in Maryland deemed it fitting and proper to give the good people a church and pastor of their own. To this end, the Rev. Joseph Greaton SJ was dispatched to the Quaker City on the Delaware in 1731.

Says the modest historian of the Messenger of the Sacred Heart of Jesus, (published at Woodstock College, Md) – “We lately found an interesting paper relating to this first visit of Father Joseph Greaton to Philadelphia. On this paper we find the following note: ‘This I have heard from Archbishop Neale, the 4th of December, 1815, the first day he was archbishop of Baltimore.’ The document itself is as follows: ‘Mr. Greaton, one of the Jesuits of Maryland, being informed that in Philadelphia there was a great number of Catholics, resolved to try to establish a mission for their spiritual comfort. In order to succeed the better, he went first to Lancaster, where he had the acquaintance by the name of Mr. Doyle. The object of his journey was to know from his friend the name of some respectable Catholic in Philadelphia, to who he could address himself, and by whom he could be seconded in his laudable exertions to found there a mission.

‘Mr. Doyle directed him to an old lady very respectable for her wealth, and still more for her attachment to the Catholic religion. Father Greaton, on his arrival in Philadelphia, presented himself dressed like a Quaker to the lady, and after the usual compliments, he turned his conversation on the great number of sectaries who were in that city. The lady made a long enumeration of them – Quakers, Presbyterians, Lutherans, Church of England members, Baptist, etc., etc. The Father then asked her: -- ‘Pray, madam, are there any of those who are called Papists?’

‘Yes,’ she replied, ‘there is a good number.’

‘Are you one?’ asked the Father.

The lady stopped a little, and then acknowledged that she was.

‘I am one, too,’ added the priest.

This gave rise to many other questions, among which was the following: Have the Catholics a Church?’ The lady answered ‘No, they have none.’

‘Do you think they would be glad to have one?’ continued Father Greaton.

‘Most certainly, sir, but the great difficulty is to find a priest.’

‘Are there no priests in America?’

‘Yes, there are some in Maryland, but it would be impossible to get priests from that quarter.’

‘No, not impossible,’ said the missionary, ‘I myself am one at your service.’

‘Is it true?’ asked the lady, with warm interest, ‘is it true that you are a priest?’

‘Yes, madam, I assure you I am a priest.’

“The good lady could not contain her joy to see after so many years a Catholic priest, and like the Samaritan whom who, having found our Lord Jesus Christ, ran to announce to the citizens of Samaria, she went through the neighborhood, and invited her Catholic acquaintances to come and see a Catholic priest in her house. This was soon filled with Catholics, for the most part Germans. Then Father Greaton began to expose to them the object of his journey. At that very meeting, a subscription was opened to raise sufficient funds to buy lots and build a Catholic church. All willingly contributed to this good work. They bought lots and a house of their hostess who acted in a very generous manner.

…..

Father Joseph Greaton … was born of a wealth Royalist family at Ilfracombe in Devonshire, England in 1680. Since the penal laws of “merry England” were still in force he was sent to the Continent for his theological studies, and there became a priest. After ordination he entered the Society of Jesus, July 5, 1708; and made his vows of solemn profession on the feast of St. Dominic, August 4, 1719.

About that date, he came into his patrimony, which appears to have been considerable; for contrary to the custom of the Society, he was granted permission to apply his inheritance to missionary purposes.

“It was with this money,” says the reverend annalist of St Joseph’s Church, that he purchased the grounds on the Nicetown Road (later renamed Hunting Park Ave), and in other places in the city and the state; and it is with Father Greaton’s money that Father Harding, at a later period, procured a large lot of ground in Fourth Street above Spruce, extending back to Fifth Street, and built the original St. Mary’s Church, Philadelphia, no appeal having been made to the faithful, and no grant having been obtained from the Proprietor (William Penn).”

…...

It was in 1731, that Father Greaton purchased a lot of ground near Fourth and south of Walnut Street, and began the erection of St. Joseph’s Chapel. It was only a room eighteen feet by twenty-two whose modest proportions might have recalled the living-room of the Holy Family at Nazareth, or the Cenacle of the Apostles at Jerusalem. It was completed in February, 1732, and the first Mass was celebrated in that primitive church on February 26th of the same year.

The chapel was so built as to seem a portion of the good Jesuit’s residence, having very much the appearance of an out-kitchen attached to the large and substantially erected mansion, which was commenced in 1732 and completed in 1733. That ancient, roomy house is still standing (in 1886) and forms a part of what is now called St. Joseph’s College. (ed.: the College later moved to 17th and Stiles, and eventually to Overbrook).

Before it was ready for occupation, the little Chapel had excited the jealous suspicions and fears of the Quakers. As early as 1708, William Penn in a letter to Governor Logan dated July 29th, reproached him with the words: “There is a complaint against your government, that you suffer publick Mass in a scandalous manner. Pray send the matter of fact for ill use is made of it against us here.”

This reproach to the contrary, it is contended by some that the Quaker founder of our State and City was secretly a friend of the Catholics, and that his protest to Logan was prompted solely by a fear of “the powers that be”.

Finding his little chapel threatened, Father Greaton appealed to the Governor for protection; but the latter gave him to understand that his only recourse was to make the basement of the Church his dwelling place. The authorities could secure him the unmolested possession of a residence, but not of a Popish Chapel. Father Greaton took the hint, and up to the time when his residence was ready for occupancy, he made his abode in St. Joseph’s basement.

But meanwhile, the vigilant Quakers were becoming convinced that active measures were needed to uproot this flourishing little plant of Popery from their exclusive center. Philadelphia might mean City of Brotherly Love to followers of Fox, -- but there was no brotherly love to spare for the offensive Romanists.

At a session of the Provisional Council, July 25, 1734, Lieutenant Governor Patrick Gordon, as president of the meeting, informed the Council “That he was under no small concern to hear that a house, lately built in Walnut Street in this city had been set apart for the exercise of the Roman Catholic Religion, commonly called the Romish Chapel, where several persons resorted on Sundays to hear Mass openly celebrated by a Popish priest. He conceived he said the public exercise of that religion to be contrary to the laws of England, some of which, particularly the 11th and 12th of King William III, are extended to all His Majesty’s dominions; but those of that persuasion here, imagining they have the right to it from some general expressions in the Charter of Privileges, granted to the inhabitants of this Government by our late Honorable Proprietor, he was desirous to know the sentiment of this Board on the subject. It was observed hereupon that if any part of the said Charter was inconsistent with the Laws of England, it could be of no force, as being contrary to the express terms of the Royal Charter to the Proprietory. But the Council having sat long, the consideration thereof was adjourned to the next meeting; and the said laws and charters were then ordered to be set before the Board.”

So the matter rested for a little while, which however must have seemed long enough to the first pastor and the people of St. Joseph’s until July 31st (feast of St Ignatius of Loyola) when the subject was reconsidered as follows:

“The minutes of the preceding Council being read and approved, the consideration of what the Governor then laid before the Board touching the Popish Chapel was resumed, and the Charter of Privileges, with the laws of the Province concerning liberty being read, and likewise the statute of the 11th and 12th of King William III, chapter 4, it was questioned whether the said statute notwithstanding the general words in it, ‘all others, His Majesty’s Dominions,’ did extend to the plantations in America and admitting it did, whether any prosecution could be carried out here by virtue thereof, while the aforesaid law of this province, passed so long since as the fourth year of her late Majesty, Queen Anne, which is five years posterior to the said statute, stands unrepealed. And under this difficulty of concluding upon anything certain in the present case, it is left to the Governor if he sees fit to represent the matter to our Superiors at home, for their advice and directions on it.” (ed.: in other words, it was a hot potato, and like all good bureaucrats they decided to pass the buck).

Nothing more was done at this time but four years later after Governor Gordon’s death, the Penn family did not hesitate to reproach his successor with his remissness in the matter, writing at that date (1738) to James Logan “It has become a reproach to your administration that you have suffered the publick celebration of the scandal of the Mass.”

Nevertheless, although those primitive City Fathers, controlled by a deliberate and temporizing spirit, are said to have taken no active measures to rid themselves of the objectionable Mass-house, tradition tells us that it was thrice leveled to the ground by the British soldiery, and was only saved a fourth time from a similar fate by the consummate prudence and address of Father Henry Neale SJ, who arrived from England in 1740, and became Father Greaton’s first assistant at St. Joseph’s on April 21, 1741.

It was doubtless this intolerance on the part of his countrymen, which led the English Jesuit to build his little chapel in such a secluded spot. Under the spreading walnut trees which gave name to the ancient street, St. Joseph’s of 1744 was close to one of the largest buildings of the times, the old Quaker Almshouse …

Its very contiguity was in itself a protection to the little “Romish Chapel” and within the distance of a quarter of a mile was then the house of our First President, the immortal Washington, he who said to a priest, (afterwards the Archbishop of Baltimore, Rev Ambrose Marechal) in allusion to a full length picture of the Blessed Virgin Mary, which hung at the head of his bed: “I cannot love the Son without honoring the Mother.”

We shall now fast-forward to 1757. In the intervening time, Fr Greaton and his assistant Fr Neale died. Also, several other Jesuit missions in upstate Pennsylvania were launched, again supported by the money from Fr Greaton’s patrimony. In his will Fr Greaton left his estate to Father Harding and it is with this priest that we shall pick up the story.

In April 1757, Father Harding gave to the Provincial authorities an account of the members of his congregation. There were then 78 females and 72 males, (mostly Irish) who were over 12 years of age and had made their First Communion. Father Schneider’s congregation consisted of 107 males and 121 females, all Germans. This large increase in the number of worshippers called for more room; and accordingly that same year (1757) the original little Chapel was pulled down to give place to a more pretentious structure running east and west, 60 by 40 feet.

The Reverend annalist of St. Joseph’s has preserved and printed an extract from the letter of a gentleman, who in his youth was a member of this modest little Chapel. He describes it as follows:

“It occupied all the ground enclosed in the modern structure. It was an oblong building …. With the ceiling arched in the center, probably not more than 20 feet high from the floor; the sides along the north and south walls having flat roofs, about 12 feet high. It had no gallery, but there was a small organ loft at the west end under the arch. The roof had its main supports from a series of posts resting in the pews of the north and south aisles. The Church was badly lighted and worse ventilated. The few windows in the north and south walls merely afforded what is termed ‘a dim religious light.’ Transgressors who sought religious grace, found in that little Chapel naught to distract their minds or their eyes, in the way of ornamental art or gaudy show. It was built for and appropriated solely to the worship of the only Superior recognized by an intelligent and consistent Catholic.”

“The walls exteriorly were rough-cast and pebble-dashed, thus throwing difficulty in the way of Young America inscribing his name thereon, for the edification and benefit of anxious inquirers or unborn millions (ed: graffiti).”

“It was an entirely plain building about 100 feet long with a flat roof on each side about 14 feet in width extending the whole length. There were probably eight windows in the north front, of medium size with old-fashioned eight-by-ten window glass in them. The entrance to the church was through a small doorway at the end of each front; and this fact seemed to create a law for those who lived up town to use the Walnut Street passageway and for those who lived in a southerly direction to use the Willings Alley gate.”

During the Revolution

On the evening of October 23, (1881) in the same church (St Josephs), took place the blessing by Rev. W. F. Clarke SJ, of a new marble tabernacle and Exposition which had been erected on the main altar of St Joseph’s in commemoration of the great event of the morning. An appropriate instruction was delivered by Fr. Clarke, and the ceremonies were brought to a close by the solemn Benediction of the Most Blessed Sacrament.

Fr. Clarke, in his masterly discourse of the morning, presented so graceful and vivid a resume of the events attendant on the surrender of Earl Cornwallis at Yorktown to General George Washington, Commander-in-Chief of the allied forces of America and France, that we cannot do better than re-frame some of his beautiful word-pictures in our present work, for the benefit of future readers:

“The focus of excitement and eagerness for news” said the reverend orator, “was this city; for Philadelphia was then the seat of government. Here Congress held its sessions, and then Congress was supreme; and here the foreign ambassadors had their residences. The French army had passed through Philadelphia on its way south in the beginning of September; but then its destination was unknown. Its reception here, on the afternoon of the 30th of August (1781) was more like a triumph than a mere passage. The whole city was in the streets in gala dress. Ladies with gayest smiles waved their handkerchiefs; men whirled their hats above their heads, and the air rang and rang again with huzzas of welcome.

On the following day after a parade which was witnessed by at least twenty thousand persons, the superior officers dined by invitation with the French Ambassador, and among them was the Ambassador’s son, Counte de Charlu, a lieutenant colonel in one of the regiments. Scarcely were they seated, when a sealed package was handed the Minister.

In a moment every tongue was silent, every eye was fixed on his Excellency, every ear attentive. In the midst of breathless silence, he announced that Count de Grasse, with the French fleet, had reached the Chesapeake. A burst of applause greeted the announcement; the news reached the streets; the Secretary of Congress, Charles Thompson, called to pay his respects and offer his congratulations; and soon the rejoicing populace gathered about the house, and added to the hilarity and enthusiasm of the guests by repeated cries of ‘Long Live the King of France’.

The French army resumed its march to victory or death. Weeks of anxious expectation passed. At midnight between the 23rd and 24th of October (1781), the clattering hoofs of a galloping steed were heard echoing along the darkened and deserted streets of the city. Its rider, Colonel Tighlmann, one of the aides-de-camp of General Washington, alighted at the door of the stately mansion on High Street (now Market Street) near Second, occupied by the Hon. Thomas McKean, then President of the Continental Congress; and full of the importance of his great mission, knocked so loudly for admittance that a watchman was about to arrest him as a disturber of the peace. That mission was to announce the capitulation of Yorktown. News of such vast public interest could not be withheld for a moment from those who, day after day, had so eagerly and anxiously expected it; and the watchmen, to whom by order of Mr. McKean it had been communicated, raising their voices to a shriller pitch than ever, aroused the sleeping inhabitants with the exhilarating cry: “Cornwallis has surrendered!”

Night was instantly converted into day; lights gleamed in every house; men, women, children rushed into the streets wild with patriotic curiosity, to learn the particulars. The State-House bell (Liberty Bell) rang out its merry peals; shout followed shout, huzza answered huzza as citizen met citizen and crowd mingled with crowd hurrying from street to street to hear or carry the news; and as the day dawned, the festive booming of cannon bore to the adjacent country glad tidings of the momentous victory.

Congress assembled at an early hour; and, though every member had heard the joyful news, they were so electrified by the words of Washington, when Secretary Thompson read his letter announcing the surrender, that they could scarce refrain from interrupting it with their acclamations. They resolved to go that day in a body to a neighboring church to thank God for the blessing he had bestowed on our arms, and appointed a committee of four to make further appropriate arrangements for honoring the victors, both officers and men, and for a celebration of the glorious event which should be national. One of the four was that signer of the Declaration of Independence who staked a far larger fortune on the result of the war than any other, the member from Catholic Maryland, Charles Carroll of Carrollton.

…..

What the warrior-nobility and gentry of France thus did at Yorktown, that their illustrious representative, the Minister Plenipotentiary of France to the United States did in this city; did in St Joseph’s Church; did on the very spot we are now commemorating the deed. At the suggestion of the committee appointed by Congress to make arrangements for the celebration of the great victory in Virginia, that august body recommended to the several States, to set apart the 13th of December to be religiously observed as a day of thanksgiving and prayer. But such was the uncontrollable enthusiasm which swayed all classes of citizens, that though that day was kept, it was also anticipated by civic and religious celebrations.

…..

And the General Superintendent of the Yorktown Centennial Association, Col. J. E. Peyton, during his visit last month to New York, speaking of the religious portion of the programme for the celebration just held at Yorktown, said: “The morning service has been assigned to the Roman Catholic Church, because his most Christian Majesty, Louis XVI., had nearly twice the number of troops in the field at Yorktown than the colonists had, and they were all Catholics. Catholic valor, Catholic blood and Catholic treasure then, contributed more than any other to that decisive blow for American Independence dealt the British at Yorktown.

The ecclesiastical celebration took place at Old St. Josephs Church on Sunday, November 4, 1781, two weeks after the celebration on the battlefield. The Church, which was filled to its utmost capacity, was brilliantly illuminated, the altar especially was ablaze with lights, and was decked with its richest ornaments. The French Ambassador invited Congress to be present, and his invitation was gladly accepted; and besides Congress, which attended in a body, headed by their President, Hon. Thomas McKean, the most distinguished inhabitants, military and civil, were likewise present. ….

Suppression and Restoration

During the period between 1773 and 1814, the Society of Jesus was suppressed. Rather than having a theological or church related impetus, the suppression was largely driven by political considerations. It started in Portugal, France and Sicily, and was carried out in all countries except Prussia and Russia where Catherine the Great had forbidden the papal decree to be executed. Because millions of Catholics (including many Jesuits) lived in the Polish western provinces of the Russian Empire, the Society was able to maintain its existence and carry on its work all through the period of suppression. Subsequently, Pope Pius VI would grant formal permission to the continuation of the Society in Russia and Poland. Based on that permission, Stanislaus Czerniewicz was elected superior of the Society in 1782. Pius VII during his captivity in France, had resolved to restore the Jesuits universally; and after his return to Rome he did so with little delay: on Aug 7, 1814, by the Bull Solicitudo omnium ecclesiarum, he reversed the suppression of the Order and therewith, the then Superior in Russia, Thaddeus Brzozowski, who had been elected in 1805, acquired universal jurisdiction.

To be sure, during the suppression, some drifted away. More typically those Jesuits who had taken vows and were ordained stayed the course and attempted to maintain some sense of community and to preserve those former Jesuit properties as well as they could. An outstanding example of this is a native born Jesuit from Upper Marlboro, Md., who was named John Carroll. He was born in 1735, joined the Society in 1753 and died in 1815, slightly after the restoration. Before the suppression occurred, he was a “praeceptor” to the son of Lord Stourton during his travels in Europe. Later he was guest and chaplain to Lord Arundell at Wardour Castle in England. When the bull of suppression was issued, Fr Carroll returned to Maryland. At the time because of laws discriminating against Catholics, there was no public Catholic Church in Maryland, and so Father Carroll along with other former Jesuits began the life of a missionary in Maryland and Virginia, using his parent’s home in Rock Creek as a headquarters. As time went on Fr Carroll and his dedicated cadre met with success, and in late 1789 he was consecrated bishop of Baltimore and later archbishop. And so, because of the dedication of one man and his followers, Baltimore became the first see in the United States.

During this time, Old St. Josephs passed from the care of the Society of Jesus and it was not until April 1833 that they were to return. During the intervening years it was in the charge of the Augustinians, the Dominicans, the Franciscans or the secular clergy. It functioned more or less as a “universal city of refuge” because at any one time members of each religious order including former Jesuits could be found living in the house in harmony each with his own rule and customs. Also Old St Josephs functioned as a Cathedral for a time starting in 1820 under Bishop Conwell. Later this function was moved to St John the Evangelist in center city, and still later to the present site on Logan Circle under Bishop (Saint) John Newman.

A “New” St. Joseph’s

So far there have been three churches on the site of Old St Josephs that we know of. The first was “Father Greaton’s Popish Chapel”. In those pre-revolutionary times when America was still a British Colony, tradition tells us that the Chapel was torn down at least three times by rioting British soldiers.

In 1757 a more permanent structure was erected on the site. It measured 60 feet by 40 feet. At the highest point the ceiling was 20 feet above the floor, and although there were no side galleries as the present church has, there was a rear gallery containing a small organ.

In 1824, March, notice was given in the papers that an enlargement of the church was necessary. Contributions were solicited. At this time the notice declared, "The chapel of St. Joseph's to be utterly disproportioned to the extensive number of the congregation and in “all respects unsuited for the purpose of divine worship."

View of Main Altar from the rear of the Church

It was not until 1838 however, that work had commenced on the new church, the present structure. By then Father Felix Barbelin was on hand as pastor. After some fund raising efforts, on Monday, May 7th, services were held in the old church for the last time. On the next morning workmen commenced demolition. On June 4th, Rev. Jas Ryder, the senior pastor of St. Joseph's, laid the corner stone of the present church in the presence of Bishop Conwell, who was blind. It rained, and the sermon had to be delivered in St. Mary's Church. In the corner stone were deposited coins, pamphlets, notes, etc., also the following declaration:

"In the Pontificate of Gregory XVI. This corner-stone of the new St. Joseph's is laid this fourth day of June, Whitsun-Monday, 1838; of the Independence of the United States, the sixty- second; Martin Van Buren, President of the United States; Joseph Ritner, Governor of Pennsylvania; John Swift, Mayor of Philadelphia; Right Rev.Henry Conwell, Bishop of the Diocese; Right Rev. Francis Patrick Kendrick, Coadjutor; Rev. Thomas F. Mulladay, Provincial of the Society of Jesus in the Province of Maryland; Rev. Jas. Ryder and Rev. Felix Joseph Barbelin, Pastors of St. Joseph's."

A record also placed in the corner-stone declared it to be "the first temple in which the hymn of thanksgiving was chanted to the God of Armies —in the presence of Washington and his staff and the representatives of France and the United States—for the blessings bestowed on the infant Republic in her struggle for right and liberty." The United States Gazette, of June 5th, 1838, has a full report of the ceremonies. The building committee members were Fathers Ryder and Barbelin, and Messrs. John Maguire, Joseph Donath, Jno. Maitland, Martin Murphy and Jno. Darragh. The present church is 72 ft. long. The present church was erected under the direction of Jno. Darragh, architect; Michael Gehegan dug the cellar; David Ryan, stone mason; Edward Carr and George Johnson, bricklayers; Jas. Carroll, marble mason; and Thomas Ryan, carpenter. The consecration of the present church took place February llth, 1839, Rev. Felix Barbelin being pastor. (ed: Washington died on Dec 14, 1799, so it is unlikely that he was present at Old St. Josephs in 1838).

The Apostle to Philadelphia

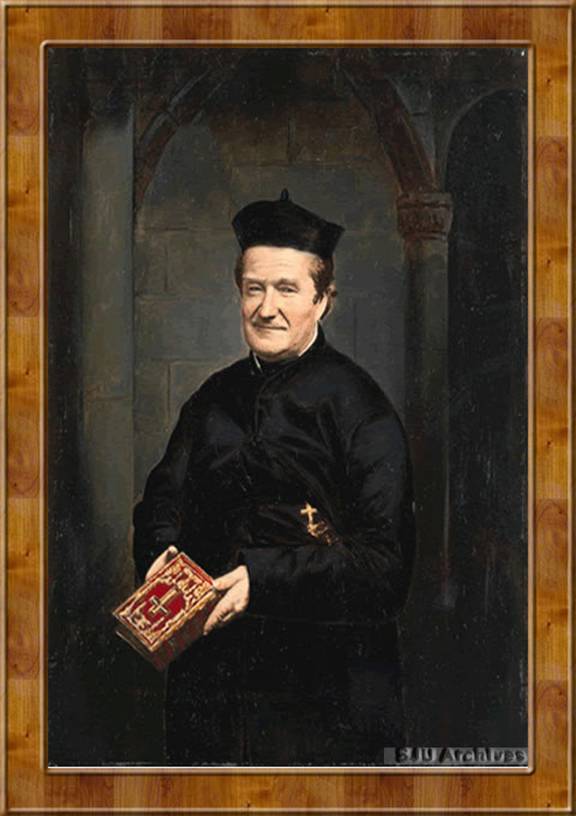

The history of the Jesuits in Philadelphia cannot be treated properly without discussing the life of one man, Father Felix Joseph Barbelin SJ. His picture is just below.

The historical context of that period was marked by strife and upheaval. The French Revolution had just concluded. The Napoleonic Wars lasted from 1804 to 1815. After all the turmoil the monarchy was restored but in 1830 the July Revolution occurred, deposing King Charles X. Back then, communication was by post rider or special messenger or sailing ship. There was no Internet or email or computer technology. No radio or TV and no electricity were available and none of the modern conveniences existed that we now take for granted. All these conditions had a significant effect on the life of young Felix.

Father Barbelin is an interesting man. There is an old Chinese curse: may you be borne into interesting times. Well, he was. He was borne in Luneville, Lorraine, France on May 30, 1808, the son of Dominic Barbelin and Elizabeth Louis Barbelin. His father was the Secretary to the Revenue Department of the district of Luneville. He was the first borne of seven children. The others were named John Peter, John Baptist, Marie, Josephine, Ignatius Xavier, and Emily. All but one became either priests or religious, and his brother Ignatius Xavier also became a Jesuit although his apostolate was in England.

In his nineteenth year he entered the seminary in Nancy, receiving minor orders in 1829 and although seminary life agreed with him, it was not destined to last too long. In 1830 the strife of the July Revolution was in full swing. Conscription was the order of the day and there were no deferments as is common today. The system was managed by lottery and all young men were required to draw numbers by lot to determine their status. Prior to this, Felix had requested a passport to come to America and when he arrived at the Prefecture to collect it, he was told that he had drawn a bad number and was required to enlist. But by some bureaucratic snafu he also received the passport, and quickly he packed and departed for Le Havre, and thence to America. The mix-up was not discovered for several days and by then it was too late.

Upon his arrival in America he landed in Norfolk and from there went to Georgetown and in January of 1831 he entered the Jesuit Novitiate at Whitemarsh, Maryland. He was ordained in September of 1835, and was appointed Assistant Pastor of Old St Joseph’s in 1838. Later in 1844 he was appointed Superior and Pastor at Old St Joseph’s.

The French had provided substantial assistance in our revolutionary war. So most of the population was favorably disposed to all things French. In part because of his personal charm, this little French priest must have proved irresistible to the Catholics in Philadelphia. He was totally unassuming with a genuine piety and I am sure he unintentionally mangled the English language with his heavy accent provoking many smiles, and thus all listeners had to concentrate twice as hard to catch his meaning. He was a shrewd individual, and he originated several movements that were destined to materially affect the Jesuits and their cause in Philadelphia. In addition to the various Sodalities and other religious works, he founded St Josephs Hospital, and St Josephs College. At the time, a ‘College’ was not an immense campus with many buildings and thousands of students. Rather, it was an “Academy” similar to our present day high schools. This was at a time when most were uneducated with barely a smattering of Basic English and Arithmetic.

THE FIRST SODALITY

To Father Barbelin is due the honor of organizing the first Sodality of the Blessed Virgin in this diocese, and the first organized in the world other than those in Catholic colleges and convents. On Monday evening, January llth, 1841, a meeting, called by Father Barbelin, S. J., was held at the church. There were seventeen youths present. All were attendants at the Sunday school, and their ages ranged from thirteen to eighteen. The purpose of the meeting is expressed in the resolution then adopted:

WHEREAS, There are many amongst us, who having made their First Communion some years since, still feel the great importance of religious instruction; and, whereas, fraternal association with one another, and union in our mutual exertions in the discharge of religious duties, would, no doubt, be a pleasing and powerful inducement to a pious perseverance; we form ourselves into a society for the purpose of reciting together our lessons, writing religious compositions and performing such other good works as we may direct.

On the following Thursday evening, Father Barbelin explained the nature of Sodalities established in the colleges of Europe, and at this meeting the Sodality was organized and the name of the Sodality of the Nativity of the Blessed Virgin was chosen—St. Stanislaus being selected as the patron—and on this evening five additional young men joined, making the number twenty-two. On the following Sunday, January 17th, the new Sodality assembled before the altar of the Blessed Virgin, in the church, and recited the Office. The formation of the Sodality was at once communicated to Rev. John Boothan, General of the Society of Jesus, and a desire expressed to be affiliated with the Sodality of the Roman College, and thus be enriched with all the indulgences and privileges granted by many Sovereign Pontiffs to the chief Sodality. The diploma, granting the request, was issued December 15th, 1841, being confirmed by Pope Gregory XVI. The document, however, did not arrive at St. Joseph's until March 28th, 1843. The first anniversary of the Sodality was celebrated Jan. 9th, 1842, the address being delivered by Rev. Jas. Ryder, at that time President of Georgetown College, who came at the request of the young Sodalists. The record reads that he spoke of "the beauty, sweetness and benefits of early piety, and exhorted them to follow the example of their holy patron —St. Stanislaus—in disdaining the pleasures of the world, and looking forward to heaven as the only place where real happiness can be enjoyed and the only prize worth contending for." On Friday, April 22d, 1842, the venerable Bishop Conwell departed this life. The Sodality assembled, find recited the Office for the Dead and attended the funeral in a body.

ANOTHER ST. JOSEPH'S

In 1867, it was announced that a "new" St. Joseph's Church would be built at Seventeenth and Stiles street (above Girard Avenue). Father Barbelin organized the Mater Admirabilis Society to collect money to pay for the lot. Upon this lot was afterwards erected the chapel first known as "New St. Joseph's," then as "The Holy Family". A great college and also a spectacular church now known as “The Church of the Gesu." was erected there, before many years passed by.

The “Native American” Riots

We now resume with the account from Eleanor Donnelly

In May, 1844, began the dark days of Philadelphia Catholicity. Nothing (as some one has remarked) is as inexplicable in its sudden rise, its rapid development and infectious outlawry as a mob in a great city. Some over-wise scientists talk learnedly of the effects of the planets, and the results of certain conjunctions of the stars as tending to excite and inflame the sanguinary passions of men, but with all due respect to science in general and to astronomy (or astrology) in particular, we are shrewdly inclined to suspect that the active principal of mob-law comes from below rather than from above, and that the blessed stars of heaven, like Koko’s flowers that bloom in the spring “have nothing to do with the case”.

Certain it is, that in 1844 in our City of Brotherly Love a religious party or mob sprang into existence whose deeds were worthy of the veriest Hun that ever followed the standard of the “Scourge of God”. The narrow and bitter bigotry of these “Natives” as they were called was fired by the indiscreet zeal of some hot-headed Catholics, and a furious religious riot ensued. There was bloody fighting with loss of life in the public streets, to say nothing of the destruction of valuable personal property and real estate.

The new Church of St. Michael and its adjacent orphanage on Second St., erected with so much labor and self denial by Rev Terence Donaghue, the last secular pastor of Old St. Joseph’s were burned to the ground. St. Augustine’s beautiful Church on North Fourth Street also fell victim to the devouring flames, and the Church of St. Philip de Neri in old Southwark was gutted out, and sacrilegiously outraged by the rioters.

St Michaels was rebuilt after the riots. The priest at the pulpit is Rev. Bill Ayres. St Michaels as it presently is:

In the universal terror and confusion which prevailed, the lives of all Catholics but especially of the priests and religious were in imminent peril. Father Barbelin was advised to disguise himself and go for a time to a place of safety, but even in those early days he was too well known not to be easily recognized. He had scarcely emerged from the Alley when a little child cried out laughing heartily, “Ha! Ha! Ha! Look at Father Barbelin in that big straw hat! How funny!” That same straw hat to this day is treasured by the family who loaned it to him in his hour of danger.

The little Church in Willing’s Alley which had known what it was in the past century to tremble under the stroke of the British soldier’s bayonet, was vaguely threatened in its turn by those so called “Native American” rioters. But when they proposed to sack it, their leaders answered “Oh! no, that little Frenchman won’t hurt anybody!” and the Church was spared for his sake.

Meanwhile, the work of destruction elsewhere had gone furiously on. The west wall of St. Augustine’s noble edifice bore the fearful legend, “The Lord Seeth.” This alone was left to tower above the charred remains of the Church, bearing testimony like a gigantic ghost to the omniscient power of the Eye of God, whilst amid the blackened debris below, lay fragments and cinders of many a costly statue, book and painting.

The city was under martial law for weeks. The Fathers at St Joseph’s prudently gathered together their sacred vessels and ornaments, and consigned them to the care of trusty persons in places of quiet security.

…..

After the excesses of that terrible May and July came a blessed, wholesome reaction in public sentiment. The municipal authorities felt keenly the disgrace of the shameful violations of law and order. The city proper made all the amends in its power, paying liberally for the damages sustained by the Augustinian Fathers, and expressing its willingness to do as much for the poor suffering Catholics of Kensington and Southwark.

Father Barbelin’s Death

In 1867, Father Barbelin was beginning to "wear out"—not in well-doing, but physically. On the Feast of his patron, St. Felix, May 30th, he said his last Mass, and on June 8th, 1869, he died. The Sodality of the Blessed Virgin adopted the following resolutions: These were sorrowful days at old St. Joseph's—sorrowful ones, indeed, for the Catholics of the city; where were they in our city who did not mourn? Who ever saw such a demonstration of love and sorrow as during the days he laid dead at the dear old place and on the day of his burial! What dead priest of our city ever had such a funeral? The streets to the Cathedral, where the Requiem Mass was celebrated, were thronged.

The Organs

According to the material I have uncovered, there was an organ in the second church, although no details have emerged about this instrument.

The first organ to be constructed for the present church was built by Henry Corrie. Unfortunately the only thing that remains of this organ is the casework. Hilbourne Roosevelt built the second organ and the Corrie façade was retained. The third organ was an instrument by an unknown builder, and unfortunately it was deemed unsatisfactory and retired. At the present time an Allen electronic organ is being used for services on a temporary basis.

A view of the Henry Corrie organ case

Recently however, The Episcopal Bishop of the Diocese of Pennsylvania has made a donation of a used organ to Old St. Josephs. According to the Director of Music, this organ previously resided in a church in Germantown, which had been closed for many years. The organ was partially disassembled and unplayable, but eminently worthy of being restored. And to make matters even more interesting, the organ is an untouched 3 manual E. M. Skinner. The donation was made with the stipulation that the organ be restored and installed in Old St Josephs intact. The plan is to finish up the project during the summer of 2008 retaining the Corrie casework. If everything works out as planned, this should be a fantastic save.

The Picture Gallery

Jesuit Residence:

The Entry:

The Entry again:

The Courtyard:

The Main Altar:

The Interior:

The Balcony:

A detail of the ceiling in the church:

Stained Glass Windows on left side:

Stained Glass Window on Upper Left Side:

Right Hand Side Gallery:

The Long Hallway inside the Residence:

A Few Final Thoughts

- In the course of researching the material for these few notes, I considered using the material on the web from the Catholic Encyclopedia among other things, including the various pre-existing websites that dealt with Old St. Josephs. I was going to amalgamate this material and present it in the usual fashion. However when I discovered the Eleanor Donnelly book on Father Barbelin I found that this was an interesting source of untouched material from colonial times which had been written from one point of view, namely to document a struggling parish on the edge of the wilderness, and a struggling religion in the new world. But, further, the actual existence of this book suggests another idea. Although about half the book deals with the colonial history of Philadelphia, the balance of the book is a description of the qualities of a certain holy man, namely Fr. Barbelin. The book is written in the florid style of a “vita sancti”, the life of a saint. To expose the history and make it palatable to modern audiences, one must leave behind the sanctified language and stick to discernable fact. But one ‘fact’ comes across loud and clear in the course of this narrative, namely that there must have been a grass roots movement of some kind to try and have Fr Barbelin promoted for canonization. Otherwise Eleanor Donnelly’s book would never have been written.

- From the earliest times, Philadelphia has been a seaport. It has always been in competition in this regard with both Baltimore to the south and New York to the north. Among other things, this competition spurred the development of our system of railroads in the east. Up until modern times with the introduction of containerized cargo handling techniques, all shipments of goods to or from any port such as Philadelphia was stowed aboard ships by hand, unloaded from ships by hand, warehoused by hand, all done by hard headed longshoremen. An entire secondary support industry of ship chandlers, dockyards, sail makers, shipwrights, rope makers, warehouses, drayage handlers, transportation systems such as railroads among others all grew up around and ultimately engulfed the colonial areas of Philadelphia, including Willing’s Alley and its environment. The people who lived here up until half way through the 1900’s were the working poor who had to be exceedingly tough to survive. When modern material handling techniques ultimately were adopted, the port facilities were moved further south along the Delaware River, to South Philadelphia near the Walt Whitman Bridge where an enormous containerized cargo handling facility was constructed. The older facilities collectively known as “The Docks” collapsed into disuse, and one by one all those support infrastructure companies went out of business or moved elsewhere. Parishes like Old Saint Joseph’s were left high and dry in a blighted area. But by great good luck, people at the grass roots began to rediscover this area and invested in local real estate, which at the time could be had for a song. The net effect was that massive projects such as Penn’s Landing and the Society Hill Towers and the Independence Mall were built. And, all those little old houses, which had been part of slums since the early 1900’s, were rehabilitated either by their owners or by real estate speculators. Now, this movement has expanded into the Northern Liberties section and the Fairmount area and Manayunk as well. At the present time, Old St. Josephs serves one of the most prosperous parts of the city and it is doing exceedingly well. And even more encouraging is the fact that the congregants are not just “gray heads” but young adults who inhabit the various high-rise apartment buildings and condos in the area.

The Author

John McEnerney studied organ with William Tapp at Incarnation Church, 5th & Lindley in Philadelphia. Later he studied with Robert Elmore for several years and while on assignment in Princeton he studied with Carl Weinrich. Robert Elmore was organist at Central Moravian Church in Bethlehem, and organist at 10th Presbyterian Church in Phila. Carl Weinrich was the head of the Organ Department at Westminster Choir College and organist at Princeton University Chapel for more than 30 years until he retired in the 1980’s. He is featured on many recordings.

Mr. McEnerney is an Electrical Engineer and Software Engineer, and a teacher of Mathematics. Organ and composition are enjoyable avocations. He is married and has as many (grand) children as the house can hold.